Encountering Dulce María

A personal note from Judith Kerman

I’ve been a poet all my life. Although I’ve published a lot of my own work, I never thought much about translating. I didn’t feel I had any particular talent for languages. Although I had studied French in school,. I didn’t particularly like reading French poetry. And I felt translators should know the language of the original, even though many poets do translations from languages they don’t read.

But in the 1980’s, preparing for a trip to Germany, I discovered to my surprise that I could learn languages fairly easily, and that I wanted to live in another culture and learn another language. Spanish was a good choice because it would be useful here at home. I studied in Michigan, and later in Mexico.

During my stay there, in the beautiful city of Morelia in Michoacán, I reached the point where I could read some Spanish, and began to browse in the poetry sections of local bookstores. Spanish poetry was a revelation - it was like listening to old records of Caruso, a beautiful distant voice singing to me through the static of misunderstanding. At a poetry workshop in Morelia led by Michoacán poet Naftali Coría, I heard Dulce María Loynaz’s poems for the first time.

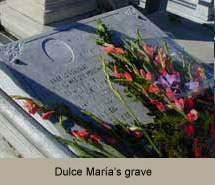

She was also clearly a major poet, a poet worth translating. To my amazement, it seemed that her work had never been published in English translation. even though she was the 1992 recipient of the Cervantes Prize, the highest award in the Spanish language. She was practically unknown in U.S. outside the Cuban-American community; even people very familiar with Latin American literature often did not know her name. Translating her for publication was clearly a worthwhile project.

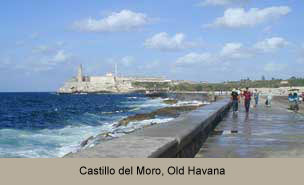

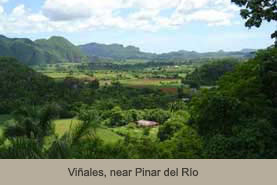

When my friends learned about my project, several said, “Why don’t you go meet her?” At first this sounded like a crazy idea–Cuba is under U.S. embargo, although only 90 miles from Florida. But I investigated, and found that it was indeed possible. And since Dulce María was already 90 years old when she won the Cervantes, it was important to do it soon.

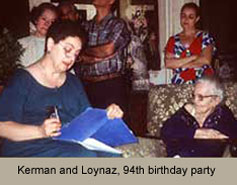

So I travelled to Cuba twice, in 1996 and 1997, to meet Dulce María and learn about her life and about Cuban society. I was able to interview many of her oldest friends and supporters, and to present a paper and read my translations at a conference in honor of her 94th birthday. She died a few months after that celebration. During those visits, the position Dulce María holds in Cuban literature and history began to become visible to me.