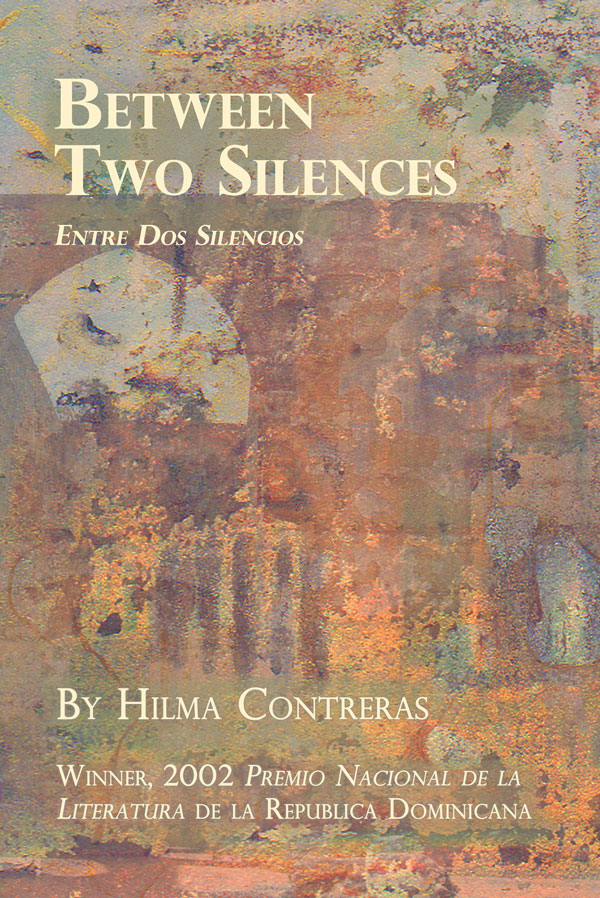

Fiction in translation (Spanish / English)

Paper, perfect bound, 122 pp

2013, ISBN 978-1-936419-31-9

$16.95 plus s&h

“Between Two Silences / Entre Dos Silencios” is a book of remarkable short stories by the great Dominican writer Hilma Contreras. These short stories (some very short) are often mysterious and quirky, with a shimmer of heat and fire, a glisten of water and a frisson which comes from not quite knowing where you are or what’s about to happen. Many stories have a sly humor and surprise endings. The reader is sometimes left with a feeling of regret, sometimes a feeling of elation and often a sense of something just out of reach.

Mayapple Press is proud to publish the first United States edition of “Between Two Silences / Entre Dos Silencios”. This collection of sixteen stories reflects the original contents and order of the 1987 book, originally published in Santo Domingo by Editora Taller. This bilingual Spanish/English edition has the Spanish on one page and the English on the facing page, making the translation come alive.

Hilma Contreras Castillo (1913-2006) was the first woman ever to win the Premio Nacional de la Literatura de la Republica Dominicana (National Prize in Literature of the Dominican Republic), the highest prize in Dominican literature, in 2002. Educated in Europe, Contreras often set her tales in a mysterious landscape, neither and both European and Caribbean. The XVI Feria Internacional del Libro (16th International Festival of the Book) Santo Domingo 2013 celebrated her Centennial.

The Window

I knew it would happen. Because of old rumors, I had lived with premonitions for a long time.

—One of these days —I would say to myself —, his habits will burn.

And they burned in slow exhalations.

It was a night as clear as the gaze of a child, in a small, silent, floating terrace, with the breath of the sea upon the four of us. Because we were four women in four towers of air. We were listening to music. The music of Liszt and our own, the music each of us carries in the blood, audible only to our own pulse.

At times — very rarely, almost never — someone’s anxiety inclines toward this subcutaneous music that nobody hears, and there it stays, dissolving in a distressing harmony.

When the lights went out, the terrace began to float in the immense blue pupil of the night. The notes of the étude departed… A sonata…

Suddenly a sharp edge of light cut the air of my tower and I began to quiver, almost to the point of breaking, my eyes drinking their existence from the illuminated window.

It was an open window, a slash in the wall’s colonial thickness, a hybrid opening somewhere between a window and an inverted skylight, through which splashes of light fell. There it was. I expected it, as one expects what should not fail. An improbably naked torso came to the window and exposed its chest.

—Are you ready? —asked a manly voice from outside.

—Yes —he replied—, but a moment more: it’s my hour for loving.

And the person turned away. It was time, like all the hours of his tormented life. How could a circle in the hair be enough to pigeonhole a life, all the long life of a hairy man!

His back to the window and to his destiny, he extended his arms. But I did not want to penetrate this far into his sin or his death. It was going to happen.

We were going to burn.

Emotion pulled my eyes away from that white wound.

There was a trembling in heaven. In slow steps the stars began to descend, they lengthened little by little in a dizzying fall, an endless long rain, over the earth.

I closed my eyes, accepting the inexorable, the body pierced by stars.

Without looking I knew that in the hanging window in the luminously quiet atmosphere, the cassock of the one whose hour had arrived had become red hot.

A flash of light burned my eyelids.

Facing me someone had just lit a cigarette, the darkest of the four of us.

Now she contemplated the mocking face of the match burning in her fingers.

—That was worth money —she commented.

But I uttered an exclamation.

The window had disappeared.

There, among the mangos of the yard, stood the old colonial house. But the wall was blind, without any window, skylight or hybrid opening.

—It seems the light from the street has gone out —said Merilinda—. You can’t see a single lit bulb.

—What a shame —I lamented—. It was the eyes of an owl that made the Father’s tonsure visible.

—Better —said the one with the cigarette—. Now we are truly alone.