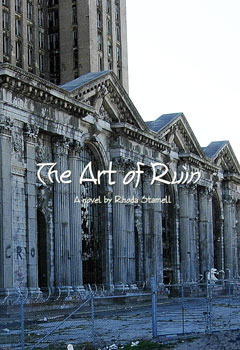

Novel. Paper, perfect bound, 126 pp

$18.95 plus s&h

2009, ISBN 978-0932412-782

The Art of Ruin by Rhoda Stamell is available on Kindle. Click here to download from Amazon

Suliman grew up as a street kid in Detroit. In jail, he began to understand himself as a man who can change things with his hands and his sense of beauty. When he meets Kate, an older woman who has always found her sense of worth in sexual relationships, she becomes his patron. Although she is unable to free herself from her own rigid sense of how things are supposed to be, Kate helps Suliman to reinvent himself as a successful artist, finding beauty and vitality in the urban landscape of Detroit.

Rhoda Stamell’s fiction contains conflicts of novel proportion. She is a conduit for disparate urban voices, jamming characters who probably should be kept away from each other, into situations where interaction is a demand as important as breath. The voices of her people are true to the ear and to themselves. These are quirky, sometimes dangerous, citizens familiar with just missed opportunities.

Chapter Six: Budgeting

by Rhoda Stamell

She is getting in too deep with this Suliman, but she can’t stop herself. She is caught up in the planning. Check bank account, go to credit union, buy a microwave for the studio. She hopes there is a stove and a refrigerator, not a hot plate and food stored on the ledge in winter. Isn’t that what artists do?

The absence of Michael, her husband, allows her to make her list at home. She couldn’t do it if he were in the house. He knows her; he would hear the pen scratching out the plans, domestic and erotic. The combination of her.

Rent: $500

Electricity/heat: $50 year-round, no AC

Groceries: $100

Paper goods: $15 (laundry detergent?)

Paints, brushes, canvases???

Telephone: $40, one phone, no extension. No phone?

Total: $705

She can’t do it without a loan even though Michael is paying his half of the house expenses. The check is always in the cup in the kitchen every month, the cup that says, “Have a Good Morning,” his half of the house payment, utilities, and taxes.

At five o’clock, she will wait outside of the Fairlane Motel. Who will care what Kate Mackey Connally does? There is no one to tell her to do anything but what she is about to do. She has complete freedom to take the remnant end of her life and make it into anything she wants.

She would like to tell someone about Suliman, but another woman would say to her what she doesn’t want to hear: our lives are not for destroying but for creating.

She could not make that woman understand that when she is with a man—in bed, or at the stove making him coffee or frying an egg, dressing and undressing for him—that is what she knows of creation. That is her way of being.

The other woman would say, “When a woman is in her fifties, her body is a vehicle to get her to the places she needs to be, not on stages where men act themselves out.”

“That’s where I want to be,” Kate would say, “on that stage. Life is nothing without a man, without the act of sex, my preference, a harsh and brutal plunging, but time enough for me to slow it down, wear it to a silken finish. That is creation too.”

She goes to Fairlane Mall. It is in Dearborn, near the motel. She can no longer figure and refigure the costs of Suliman.

The two thousand dollars is in an envelope marked “debt.” She has written a check at the credit union, her last instant loan. The loan board does not have to decide. Should we let this teacher have two thousand dollars so that she can finance a young black man about whom she knows absolutely nothing, has never even kissed him or touched his hand, and he will be doing her a favor, no matter what he does for her because isn’t the game over, look at her birth date, 1949.

Where did the money go? Casey had taken care of her expenses until he got sick, but where did her salary go? Then she lived on her own, the best time of her life because Casey was dying and yes, she felt horrible, but she was free, and every day was like being in a garden where she could pick anything she wanted. Saturdays looking for an antique show. Or going to Windsor and smuggling in a pair of shoes for the thrill of flirting with the customs officer so that he never would ask: “What do you have in the trunk of your car, fire arms, alcohol, drugs?” And the men. What is your pleasure? It will be mine.

She once enjoyed shopping in the big malls, but now she has a careful clothing budget that only allows for a small fling, a sweater, a bracelet, a nightgown.

“Rule, girls. No expenditure over $100 without a family conference. You and your husband—these days she would have to say partner, fiancé, significant other—must discuss the purchase of a major item, a couch, television, suit, winter coat. Try to shop at the end of the season. Being careless with money brings nothing but trouble. Don’t kid yourself. The mismanagement of money can break a marriage. You only have two choices: go to work or practice thrift.”

Rhoda Stamell considers herself a lifetime Detroiter. She has spent her entire adult life as an educator in Detroit, which has been the source of her fiction. Stamell began writing seriously when she was fifty years old and divides her time between writing in her home in suburban Detroit and teaching as an adjunct professor of Composition.